I recently returned from a trip to Turkey. I had traveled to Turkey in 2003 with my friend Elaine and wanted to visit again to experience more of this fascinating country. My traveling companions on this trip were long-time friends Rob and Sonya and Sonya’s long-time friend Carey.

In 2003 Turkey seemed like a second-class country. It was striving to meet European standards but not quite making the grade. We ran into problems like ATM machines that didn’t work properly and a rental car with an “air conditioning” system that only blasted hot air.

In 2024 Turkey seems to have finally achieved first-world status. The transportation system is modern. Istanbul now has a subway and not one but two tram systems. On our trip the planes, local and long-distance buses, and train we took were on time and comfortable (although the train car seemed a bit sad). The hotels we stayed in had state-of-the art whisper-quiet cooling systems, a far cry above similar systems in American motels.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his party came to power in 2003. Over the last 20 years their policies have boosted economic growth and improved Turkey’s infrastructure. (Some of these gains have been reversed in recent years.)

Erdogan won reelection in 2023 on a nationalist platform, talking about restoring Turkey to its former glory (think Ottoman Empire). As the Los Angeles Times characterized it, “In short: Make Turkey great again.” Does that sound familiar?

One of our guides railed against Erdogan. He complained about high inflation and poor economic policies. Worse, he said Erdogan is like Donald Trump, working to return women to traditional roles, make Turkey more religious, attack religious and ethnic minorities, and create an authoritarian state.

We saw evidence of nationalism with Turkish flags flying everywhere, especially in Istanbul. I don’t recall that in 2003.

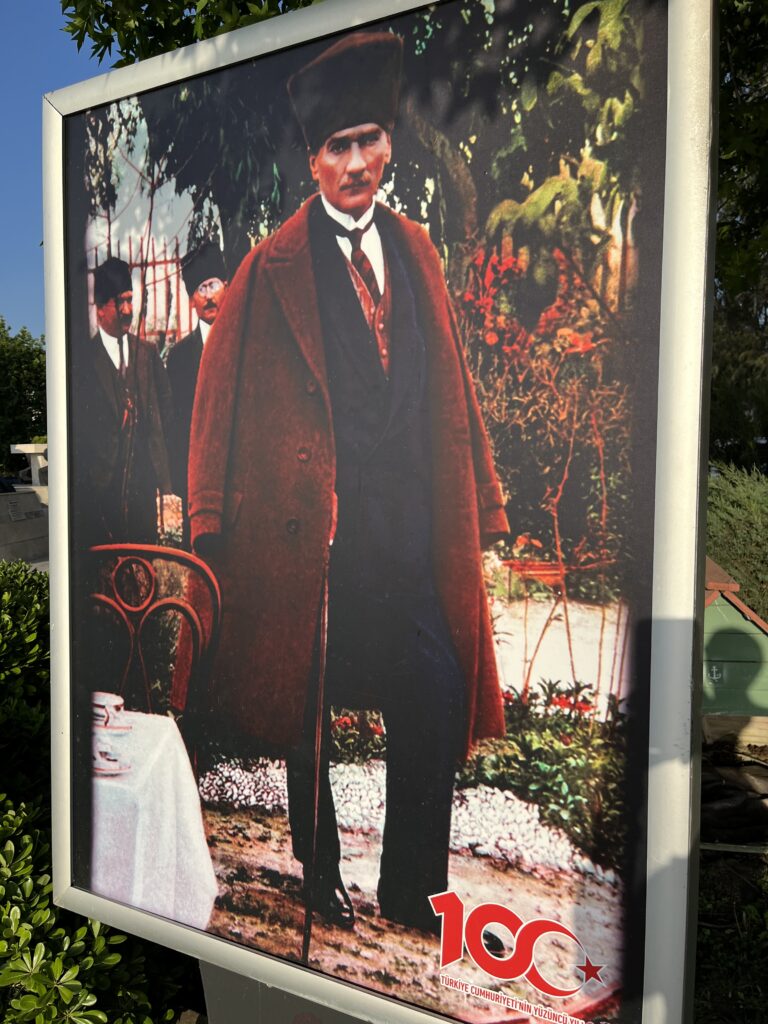

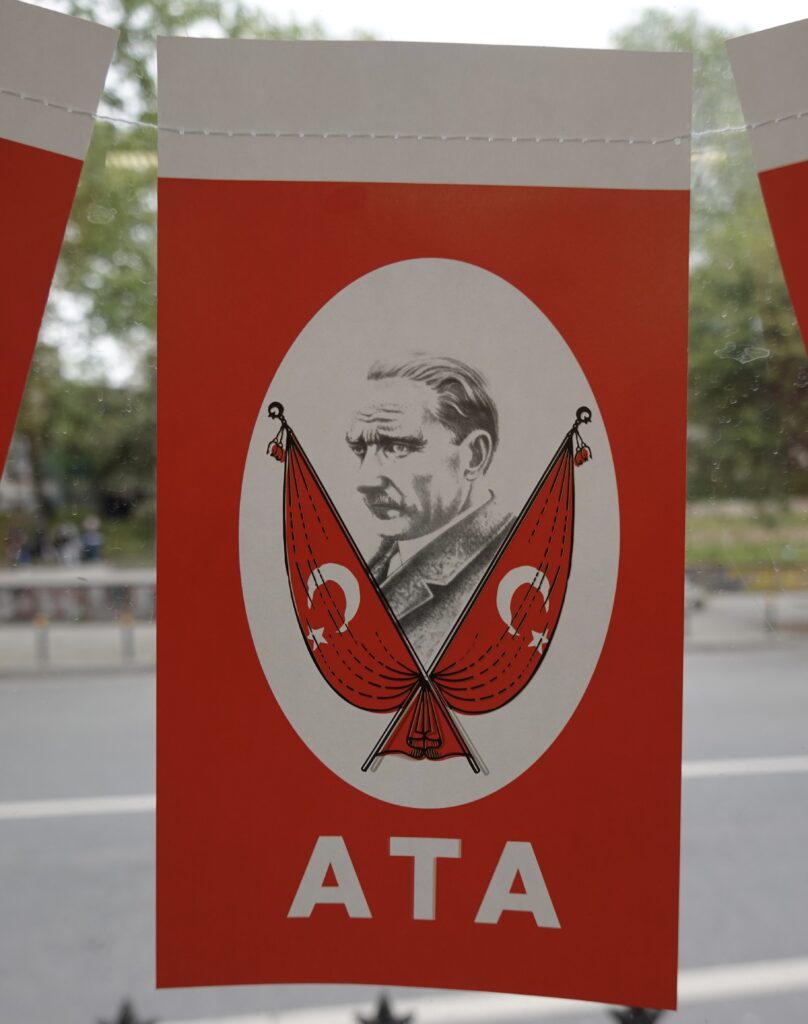

In 2023 Turkey celebrated the centennial of the Turkish Republic. We saw many centennial posters featuring Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s face. I had heard of Atatürk but knew very little about him. I was curious: Who was he? How did he help create modern Turkey?

World War I

To answer those questions, we need to start with World War I. Before my trip I picked up a novel called Birds Without Wings by Louis de Bernières (he also wrote Corelli’s Mandolin). It takes place in the time during and after World War I when Turkey threw off the remains of the Ottoman Empire and became a republic. Its storyline follows several people living in a fictional small village. It also tells the story of the rise of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

Kemal became a national hero after the Gallipoli campaign in World War I. His strategy led a handful of poorly equipped Turkish forces to successfully defend the peninsula from a huge armada of forces, primarily from the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC). The campaign was disastrous for the Allies, although both sides faced heavy losses.

I’m sure you’ve read stories about the horrors of World War I, and perhaps you saw Peter Weir’s award-winning film Gallipoli. The Gallipoli campaign had the additional challenge of disease. Many soldiers contracted dysentery and typhoid because of poor sanitation, scores of unburied bodies and swarms of flies from the corpses.

In Birds Without Wings, a young man from the village fought at Gallipoli. In one of his letters home, he wrote:

“If you are a soldier, you are forced to think about God more than those who are at home. All around you is death and devastation. You look at a disemboweled body, and you see that man consists of coils of slime inside, and yet he is smooth and beautiful on the outside. You look at a body and you see that it is not a man because the spirit has fled, and so the body does not fill you with grief. You believe that God caused every second of your destiny to be written on the fortieth day after conception, and so you do not complain about hardship and horror . . . .”

Anzac Day is an important day of remembrance of veterans and victims of war. I met an Australian couple in my hotel in Istanbul. They were part of a large group of Australians on their way to the Gallipoli peninsula to commemorate Anzac Day on April 25, the day of the Gallipoli landings in 1915.

The birth of modern Turkey

The Ottoman Empire had aligned with Germany during the war. After the war, the Allies planned to divide up the Ottoman Empire. The Greeks launched a campaign into Turkey, attempting to claim territory promised to them by the Allies. The Greco-Turkish War lasted from 1919-1922. In the end Kemal and his forces were victorious. Their next actions were to abolish the Ottoman Sultanate and, in 1923, to create the Turkish Republic.

Kemal was the first president of the new republic. The Turkish Parliament dubbed him Atatürk, which means “Father of the Turks.” According to Rick Steves, “Considered the George Washington of the Turks, Atatürk almost single-handedly created modern-day Turkey from the battle-torn, corrupt, demoralized remnants of the Ottoman Empire.” The new government adopted reforms aimed at creating a modern, western, secular country.

“Rarely in history has anyone exerted such power with such effect in so short a time,” Steves said. “In less than 10 years, Atatürk…

- aligned Turkey with the West rather than the East

- separated religion and state (by removing Islam as the state religion and upholding civil law over Islamic law)

- adopted the Western calendar

- decreed that Turks should have surnames, similar to Western custom

- changed the alphabet from Arabic script to Roman letters

- distanced Turkey from the corrupt Ottoman Empire by abolishing the sultanate and caliphate, and outlawing the fez and veil

- abolished polygamy, and

- emancipated women (at least on paper).”

The Turks love Atatürk and consider him “the greatest Turk.” Steves said, “For a generation, many young Turkish women actually worried that they’d never be able to really love a man as they already had so much love for the father of their country.”

Population exchange

Near the end of Birds Without Wings, the Greek Orthodox Christians living in the book’s small town are forcibly removed and sent to Crete. Turkish Muslims later arrive in the village, having been forcibly removed from Greece.

While the characters are fictional, the population exchange between Greece and Turkey was real. In one of his first diplomatic acts as representative of the new republic, Atatürk negotiated and signed the “Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations” in 1923 with the government of Greece.

The exchange, based solely on religious identity, involved about 1.2 million Christians deported from Turkey to Greece and about 400,000 Muslims deported from Greece to Turkey. The exchange was meant to reduce ethnic tensions and prevent attacks against minority populations. Since there were smaller numbers of Turks arriving than Greeks leaving, some towns were abandoned.

While in Turkey we walked through Kayakoy, which de Bernières used as the basis for the book’s village. It was eerie to walk through the crumbling walls of an abandoned town.

From a Wikipedia entry about Birds Without Wings: “Since then, the village of Kayakoy, as it is called in Turkish, or Karmylassos, as it was called in Greek, which had been continually inhabited since at least the 13th century, has stood empty and crumbling, with only the breeze from the mountains and mist from the sea blowing through its empty houses and streets.”

In Birds Without Wings, some of the people locked their houses when they left for Greece and handed the keys to their neighbors for safekeeping. No one ever came to live in those homes.

Here is a passage from the novel:

“In their houses, the Christians attempted to deal with the bewildering and impossible task of working out what to take.

. . . It was one of those exceeding rare occasions when blessed indeed are the poor, for by far the greater proportion of the people lived in such straitened circumstances that there were relatively few choices to make.”

“And when the people came home from seeing the Christians leave . . . for days afterwards all you heard at night was the crying of the cats.

‘ . . . .and they were wandering about, distressed, crying that low moaning cry and some of them wailing, and it was a terrible sound and it was frightening and I lay on my pallet listening to them, and I couldn’t sleep, and I understood why they were crying in the great sudden loneliness and strangeness of the town, and that is what I remember more than anything else, the crying of the cats.'”

This is great, Annette, great writing and great memories!